"The Negro: His Present Status and Outlook" (1918)

One of Debs's longest writings on black liberation, excoriating the crimes of racial tyranny and calling for independent black worker organizing.

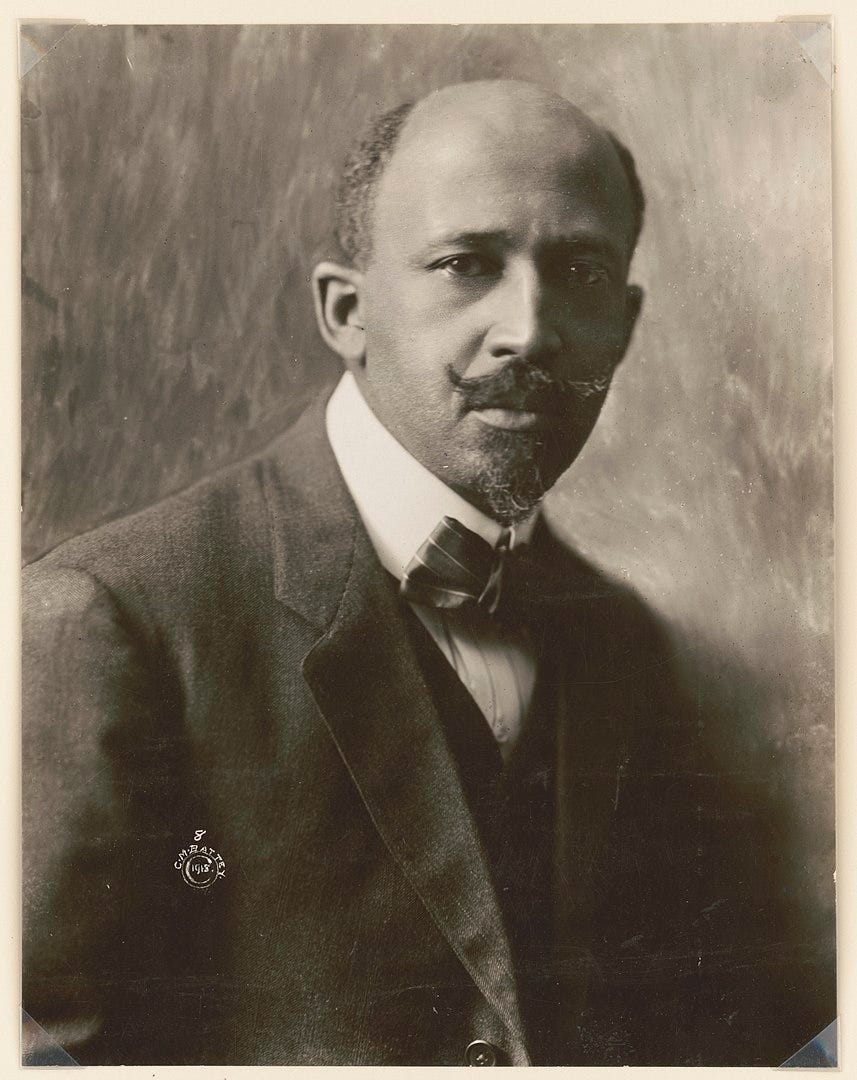

The leading article in the Intercollegiate Socialist for December-January 1917-18 on “The Problem of Problems” by Prof. W. E. B. Du Bois, dealing with the negro question in the United States, deserves wide reading and sympathetic consideration. It presents the negro question to the American people from the standpoint of the negro himself and as an issue of commanding importance which the nation can no longer ignore or palter with save at its own peril.

In speaking for the negro Dr. Du Bois stands squarely upon the negro’s rights as a human being, which rights have been shamelessly outraged from the day the first African natives, stolen by pirates from their native land, set foot upon American soil and were sold into slavery by their brutal captors.

The whole history of the American slave trade and of African slavey in the United States, clear down to the present day, is black with infamy and crime against the negro, which the white race can never atone for in time or eternity. Most of this revolting history has never been written and little of what has been written has been allowed to reach the people. Not one person in a thousand knows the facts about the stealing of the negroes by the pirates that supplied the American colonies with their black slaves; about how men, women and children were driven aboard the pirate ships, corralled like beasts, in filth, half-starved, naked, their backs scarred and bleeding from the cruel strokes of the keeper’s lash, and half or two-thirds or even more of them dying from torture on the voyage and their dead bodies cast into the sea as so many dead dogs.

This was the beginnings of the monstrous crime against the African negro by the white settlers of the American colonies—the crime that lay at the foundation of the infinitely greater crime of chattel slavery which grew out of it and which had to be expiated in rivers of blood drawn by the sword from white men’s veins—the crime of three centuries without a parallel in history.

But only a minor part of this crime of crimes committed against a race has ever been atoned for, complete restitution for which can never be made.

Never do I see a negro but my heart goes out to him and I feel like apologizing abjectly to my black brother for the crime and outrages perpetrated upon his race by the race to which I belong. I look into his starved, brutalized features, his dumb despair, and I read the tragic story of his foul betrayal and shameless spoliation of body and soul, traced there by the hand of the Almighty as the ghastly indictment of the white man for his unspeakable cruelty toward his black brother.

But I am not to deal with the past in this writing, save only as a background for the present status and the future prospect of the twelve million negroes now in the United States. Professor Du Bois has made an initial contribution to this great question which places the issue squarely before the American people, and he insists that that they shall face it and deal with it as an enlightened nation should deal with a national problem which has become so grave as to menace its very existence.

Professor Du Bois speaks out with becoming courage and candor. There is none of the apologetic spirit of Booker Washington in his attitude. He is admirably conscious of the rectitude of his purpose and the righteousness of his cause, and every word in his stirring appeal in behalf of the negro merits hearty approval and appreciation.

Dr. Du Bois has just cause to find fault with all the various schemes for ending the great war and bringing lasting democratic peace to the world, which schemes have nothing whatever to offer to the negroes and other races despoiled and held in subjection by the white race. Says Mr. Du Bois:

In the peace proposals that are now being made continually, the future of the natives of Africa, the future of the disenfranchised Indians of the Eastern and Western Hemisphere, and the disenfranchised element of the negroes of the United States has not only no important part but practically no thought. What you are asking for is a peace among white folk with the inevitable result that they will have more leisure and inclination to continue their despoiling of yellow, red, brown and black folk.

Quite right! There is thought for the Belgians, the French, the Italians and even the Germans but none for the twelve million American negroes who are nominally citizens of the republic, yet most of whom have been stripped of their franchise by the rape of their constitutional guarantees and who, in the general reckoning of those who prate about war for humanity and democratic peace, are to remain “damned n*****s,” or at best “n*****s” merely; on a dead level with other beasts of burden.

Freedom of speech is another phase of the question which takes little heed of the rights of negroes to the treatment due to human beings, to say nothing of free men, as Professor Du Bois so pointedly and pertinently says:

You are taking up the problem of the freedom of speech. Many of you are vastly upset by the increasing difficulty which you have in discussing the war in America; but I should be much more impressed by your indignation if I did not realize that the greatest lack in freedom of discussion of American problems comes not in problems you are not allowed to discuss but rather in those which you are free to discuss but afraid of. I know and you know that the conspiracy of silence that surrounds the negro problem in the United States arises because you do not dare, you are without the moral courage to discuss it frankly, and when I say you I refer not merely to the conservative reactionary elements of the nation but rather to the very elements represented in a conference like this, supposed to be forward-looking and radical.

These words are as true as they are courageous and commendable. Even among Socialists the negro question is treated with a timidity bordering on cowardice which contrasts painfully with the principles of freedom and equality proclaimed as cardinal in their movement.

There is but one way for Socialists to deal with the negro and that is to regard him as a human being, the equal in point of rights and opportunities of every other human being on earth. If he is less cultured it is because he has been robbed and despoiled by the more cultured, and this instead of militating against him but accentuates his claim to decent consideration.

The negro asks no favors; he seeks no privileges; he spurns the white man’s supercilious airs and patronizing cant. As a matter of fact he owes the white man little but his contempt. The very crimes he commits spring from the seed sown in his brain and heart centuries ago by the white thief who stole him from his native land, lashed him as if he had been a beast, exploited him to the marrow of his bones, and did all in his power to sink him to the level of a brute.

All the negro requires is that he be recognized as a human being and treated as a man. That is absolutely all. Nothing less will and nothing less should satisfy him; and nothing less will ever solve the problem and remove this growing menace to the nation.

The Socialist who will not speak out fearlessly for the negro’s right to work and live, to develop his manhood, educate his children, and fulfill his destiny on terms of equality with the white man misconceives the movement he pretends to serve or lacks the courage to live up to its principles.

The negro is “backward” because he never had a chance to to be forward. He has been captured, overpowered, put in chains, plundered, brutalized and perverted to the last degree. That is why he is backward. All he needs is environment, opportunity, incentive, the rights of a human being, the treatment due a man, the chance to do his best—and he will take care of the rest, and when final accounts are cast up he will have no reason to blush when comparison of results is made with his erstwhile white “superior.”

The negro is entitled to exactly the same economic, political, social and moral rights that the white man has, and until these are fully recognized and freely accorded all our talk about democracy and freedom is a vulgar sham and false pretense.

The negro is my brother. The color of his skin is no more to me than the color of his hair or eyes. He is a human and that is enough. I refuse any advantage over him and I spurn any right denied him, and this must be the attitude of the Socialist movement if it is to win the negro to its standard and prove itself worthy of his confidence and support.

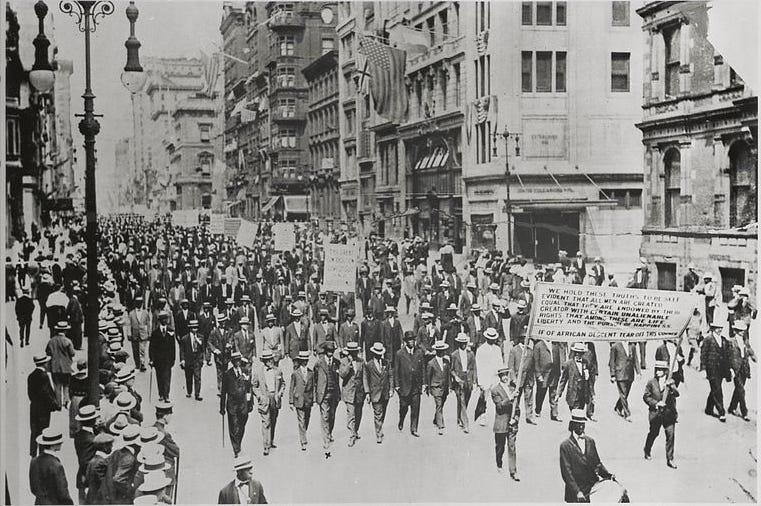

Professor Du Bois touches briefly upon the summary execution of the negro soldiers of the 24th Infantry at Houston and the infamous massacre of the black innocents at East St. Louis, the former to placate the anti-negro sentiment of the South and the latter to glut the savage lust of corporate greed and incidentally to put a foul blot upon the American labor movement.

The cowardly attitude of the American Federation of Labor toward the negro during the last twenty-five years explains in a large measure the barbarous massacre at East St. Louis.

Only within a few months has the American labor movement opened, reluctantly enough, a back door through which the negro may now meekly enter and take a back seat, and even this door had to be forced by the stern logic of events of which the appalling tragedy at East St. Louis is a chapter written in the blood of negro women and children slain by their murderous white neighbors. Had the labor unions freely opened their doors to the negro instead of barring him out and, in alliance with the master class, conspiring to make a pariah of him and forcing him, in spite of himself, to become a a scab and strike-breaker, the atrocious crime at East St. Louis would never have blackened the pages of American history.

The negro is just as responsive as the white man to decent treatment; just as susceptible to the touch of kindness; just as eager to prove himself a man possessed of character and honor, if but given the chance.

Some twenty-five years ago I was on an organizing trip in Kentucky. At Louisville I appealed to the white railroad men to admit the negro shop and track laborers to their union. They refused. A few days later the white men struck. The negroes, though insulted and repelled by the union, came out to a man. The white men, fearing the strike might be lost, rushed back to their jobs and defeated the strike. The negroes stayed out and lost their jobs.

This proves conclusively, without a doubt, that negroes are a degenerate race; that they lack character and are depraved; that they ought to pay first class fare and ride in cattle cars; that they are fit only for menial service such as blacking white men’s boots, emptying their cuspidors, and waiting on them as lackeys; that there should be rejoicing in the community when one of them is lynched or burnt at the stake, even if innocent, and that the vilest creature in a white skin is still measurably the superior of an enlightened, cultured and self-respecting negro.

In closing let me say to these black brethren of ours that their salvation, after all, lies with themselves. The overwhelming majority of them are working people and they represent more than one-tenth of our entire population. They need to get together, to stand together and assert their united power industrially and politically in behalf of their class. Like the white wage-slaves they need the light, the light of education; they require power, the power of knowledge, and this light they must generate and this power they must develop within themselves. They will progress and command respect in proportion as they are enlightened and organized, and have unity of purpose and the power to enforce their demands. Then and then only will they take their rightful place in society and have equal voice with all others in the control of the nation and in realizing the ideals of civilized humanity.