Debs, Race, and the Pullman Porters

In recent months, I’ve put writing on the back burner and focused on plumbing the archives, both digital and physical. Two subjects have consumed my time: Debs’s solidarity efforts during the early years of the Mexican Revolution (the first major instance of his internationalism pre–World War I) and his late-life radicalization on the “race question” (long a racial egalitarian, in the last ten years of his life Debs’s words grew more strident and his position more uncompromising on US apartheid).

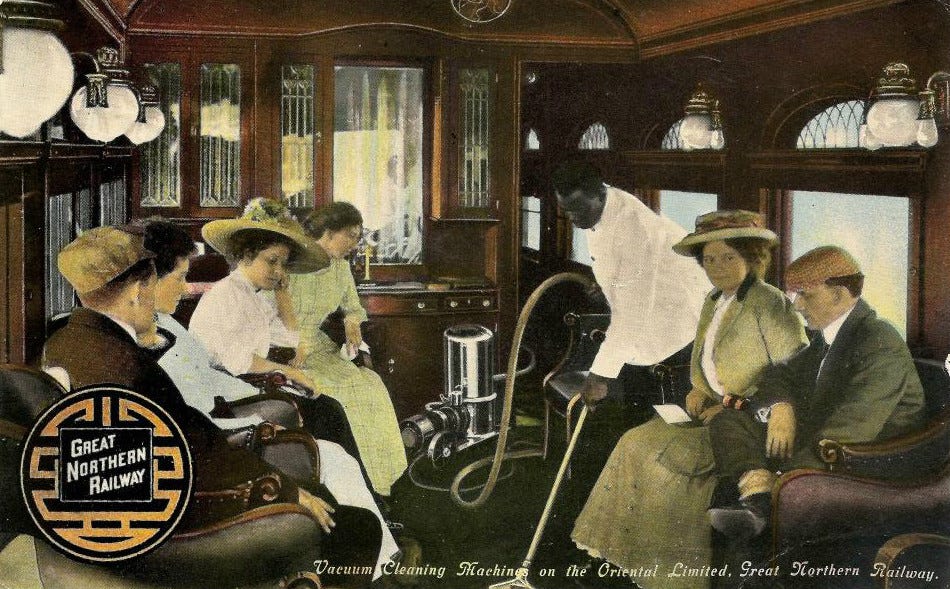

The second line of inquiry — almost entirely overlooked in previous biographies of Debs — turned up this fascinating nugget: a letter to Debs from the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters dated July 15, 1926, mere months before his October death. After alerting Debs about the union’s incipient attempt to organize Pullman porters — the all-black workforce that tended to passengers on railroad sleeping cars — the letter writers invite Debs to give the keynote speech at the union’s first convention. Tragically, he passed away before he could make good on their request.

The letter is super interesting for a number of reasons.

First, as the message notes, it was the Pullman Company “which was responsible for [Debs] going to prison” during the 1894 Pullman Strike, the titanic struggle that propelled Debs onto the national stage, turned him into a socialist, and made him a bete noire of conservative opinion-makers. (Years after the strike, you can still find derisive references to Debs in newspapers as a ruinous, tyrannical labor leader.) During the Pullman walkout — which shut down rail lines throughout the country —Debs exhorted the striking white workers to welcome the black Pullman porters into their ranks. They refused. The strike was crushed.

Second, the letter speaks to Debs’s relationship with the great civil rights and union leader A. Philip Randolph, listed on the letterhead as the sleeping car porters’ general organizer. Several years earlier, Debs had befriended Randolph when the young Harlemite was co-editing the black socialist magazine The Messenger (“the most able and the most dangerous of all Negro publications,” a spooked Justice Department fumed in 1919). The Messenger had started publishing in 1917, making a name for itself with its attacks on “Old Crowd” black leaders like Booker T. Washington and staunch opposition to World War I. Randolph’s magazine routinely praised Debs as a champion of black rights, even crowning him “greater than Lincoln.” (“Lincoln merely nominally freed the bodies of Negroes… Debs would free the bodies and minds of Negroes.”) At Randolph’s invitation, Debs travelled to Harlem in 1923 to give a long speech about black workers and socialism. And when Randolph’s biographer interviewed the now-elder-statesmen in the late 1960s/ early ’70s, Randolph said he had the “greatest admiration” for Debs, especially “Debs’s position on the Negro, his belief that the best chance for the elimination of racial injustice, which was rooted in the competitive economic system, lay in the socialization and democratization of the system.”

Third (though I could probably go on), the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was a driving force behind the radicalization of black politics after World War I. It was a shift that Debs himself had encouraged. For years, Booker T. Washington had been the grandee of black politics, at once the purveyor and embodiment of a conservative brand of racial uplift that preached accommodation to white supremacy and hostility to trade unionism. Even as Jim Crow tightened its tyrannical hold on the South, Washington counseled African Americans to get educated, keep their heads down, and make themselves useful to white philanthropists and business leaders.

Debs would have none of this. While he lamented the exclusionary policies of the mainstream labor movement (most unions either prohibited black membership or relegated black workers to segregated locals), he insisted that black workers must join their white working-class brethren in the union movement to achieve true freedom. “Does not Mr. Washington advocate the meekness and humility of the Negro race and their respectful obedience to their exploiting masters?” he wrote in 1903.

Once Debs became a socialist (he announced his conversion on New Year’s Day 1897), he never wavered in his view that African Americans were fundamentally equal to whites. In the very article often cited as evidence of Debs’s “class reductionism” — his offending statement: Socialists have “nothing special to offer the Negro” — Debs offered this ringing declaration of racial equality:

Socialists should with pride proclaim their sympathy with and fealty to the black race, and if any there be who hesitate to avow themselves in the face of ignorant and unreasoning prejudice, they lack the true spirit of the slavery-destroying revolutionary movement.

The voice of socialism must be as inspiring music to the ears of those in bondage, especially the weak black brethren, doubly enslaved, who are bowed to the earth and groan in despair beneath the burden of the centuries.

Still, in his early years as a socialist leader, Debs tended to overlook, or was perhaps slow to recognize, the newer forms of racial tyranny that Jim Crow had spawned. While Debs periodically condemned individual episodes of racist violence, he didn’t integrate them into his broader understanding of US society or pay close attention to the “race question” in his writings or speeches. He seemed content to offer an overarching prescription (socialism), reassured by the belief that racist practices, at least in the South, would subside as economic progress snuffed out the relics of plantation society. “The South is of course behind the times,” he wrote in the fall of 1903 after a lecture tour below the Mason-Dixon, “but the lingering old customs will be improved with the industrial and commercial development of that section.”

That began to change in 1916 when Debs witnessed the rapturous praise for Birth of a Nation, the virulently racist film that packed theaters with its “Lost Cause” denunciations of Reconstruction. Debs called for protests against the movie, and a stream of letters poured in from African Americans around the country (including Ida B. Wells) praising Debs for his bold stance. Over the next two years, Debs made more connections with black socialists (including the Indiana-based orator Ross D. Brown, who would visit Debs in prison in 1920), and his columns overflowed with accounts of racist terror and acerbic mockeries of white supremacy.

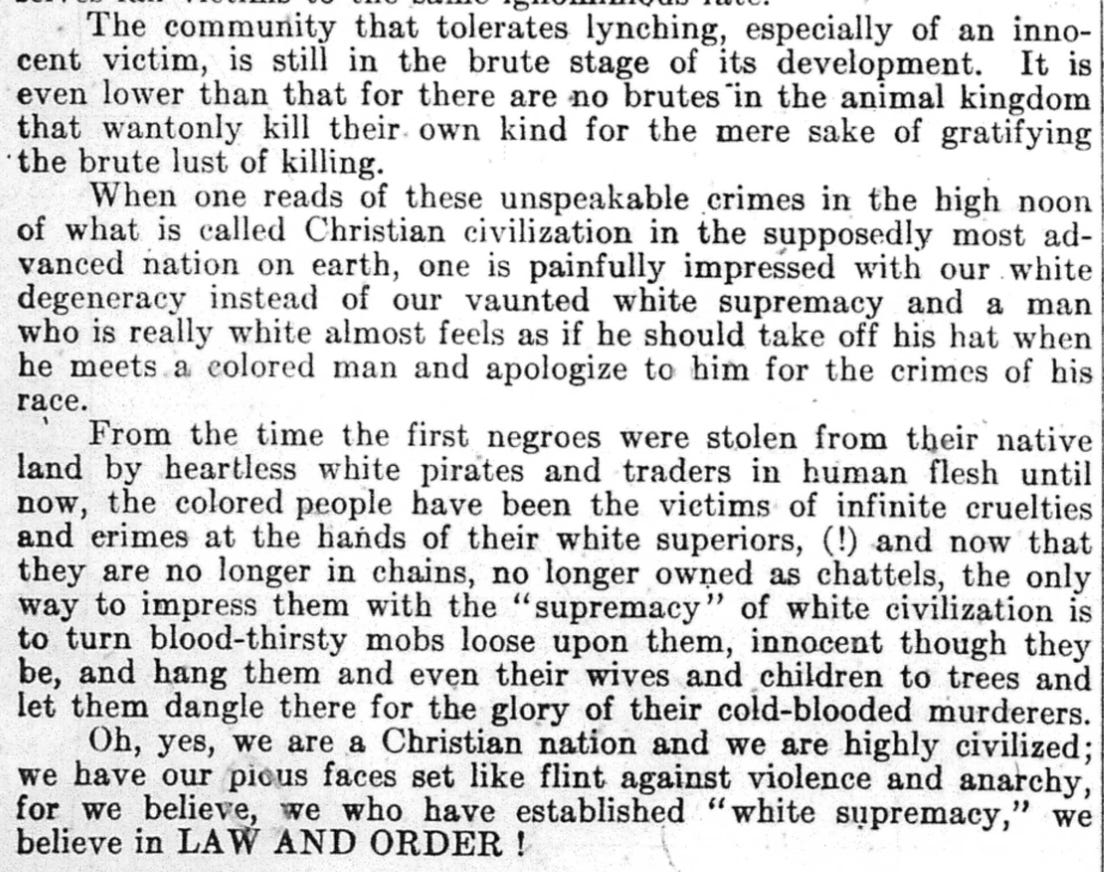

Here’s the end of one such column, published in 1917:

Debs began to recognize the need for independent black organizing, rooted in a broader working-class and socialist movement. By the 1920 election, the most militant elements of the “New Negro” movement were endorsing Debs’s candidacy. The Crusader, edited by future Communist Cyril Briggs, celebrated Debs as someone “who has always spoken out for the Negro, a man who several times has refused invitations to speak to white audiences when it was hinted that it would be best to leave the Negro out his discussion.”

I’ll have much more to say about Debs’s late-life radicalization (particularly in the book), but I’ll leave you with this quote, from a leading black newspaper’s obituary of Debs:

“That Eugene V. Debs, who as President of the American Railway Union, first led the fight on the industrial autocracy maintained by the Pullman Company in [1894], should have lived to see the lowly porters employed by that company organized into a strong, militant union, was eminently fitting and proper. Peace to his Soul.”